Cutter’s Way

(versão em português aqui)

The way to get me interested in anything is to tell me it’s impossible to make. – Ivan Passer

Czech filmmaker Ivan Passer died last thursday.I have written about him here before and there’s few careers that fascinate me more in recent decades.He directed one of the best films of the local New Wave (Intimate Lighting) and co-wrote the first Milos Forman films (Loves of a Blonde, The Fireman’s Ball, Audition), then emigrated to the West post Prague Spring like so many other Eastern European talents and things become much more odd and subterranean.Between 1971 and 2000, Passer directed 13 films, occasionally working with famous stars (Michael Caine, Jeff Bridges, Peter O’Toole, Robert Duvall, Omar Sharif) almost always in their films that no one has seen.Three decades as a kind of ghost of East European absurdism in Hollywood.

Part of what makes Passer’s Western work particularly difficult to accept is precisely the mismatch between the often harsh themes and a sensitivity that always keeps a foot in comedy.Passer’s first American film, Born to Win, about a heroin-addicted hairdresser played by George Segal who spends the days looking for the next sting sets this unlikely tone.It’s a pretty tough addiction movie, but mostly devoid of the usual condescension of the genre, very close to its central character and feeling no need to look at him from way up.Jonathan Rosenbaum suggested that the movie was a kind of black comedy about how Seagal’s character is a motivated person and has its own sort of fulfilling life by way of the same addiction that makes him a social pariah.The film is too harsh to be described as a comedy, but Rosenbaum’s remark goes to the heart of this contradiction and how Passer’s absurd sensitivity helps produce a peculiar look at his characters and their worlds.

Rarely does Passer use his eye for the aburd for a clearly comic use.A favorite of mine is Silver Bears, a caper comedy with Michael Caine running a bank devoid of actual money.The central idea of the parallelism between banking and gangsterism could not be clearer, and Passer finds a number of variations for it and in Caine someone with the easy tongue to sell any bullshit shamelessness.It’s a very funny movie that has aged very well for obvious reasons and has a stronger script (by Peter Stone who wrote Charade among others) in the scene by scene basis than most of the ones that Passer worked with, but as always when Passer works at pure comedy things are not animated by the same tightrope tension.

I remember watching a little TV movie of his, Fourth Story from 1991, and thinking about how much his career reminded me of Edgar G. Ulmer’s (if without the frenetic production pace that working in the 40s PRC allowed), that encounter between a very European sensibility, caustic gaze and staging intelligence applied to often dubious material.If Ulmer was the ghost of Murnau haunting the forgotten lower places of American cinema in the 30’s-50’s, Passer was the ghost of communist Europe and its certainty of an out of place world strolling through the basements of American cinema between the 70’s and 90’s. As time went by his materials become more and more eccentric (Haunted Summer, Creator) and he spent most of the 90s making television films that time have forgot from literary adaptations (Picnic, Kidnapped) to a Stalin’s biopic to a neonoir like Fourth Story so relaxed and dedicated to the artifice of each scene that his detective spends more time acting like a lead from a romantic comedy than solving his case.

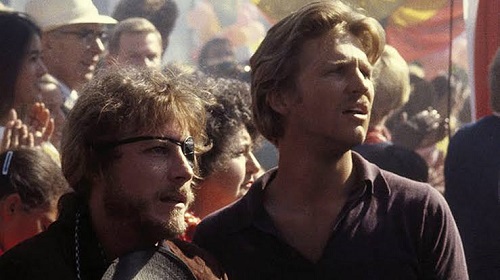

Following the Ulmer analogy, Cutter’s Way (1981) would certainly be his Detour, his one film that exists at least on the periphery of the canon and in which his sensibility received the ideal material.And even that movie was almost erased after a one-week theatrical run in a combination of a broken studio post Heaven’s Gate and a negative New York Times review that convinced them that the movie was doomed to failure. It has hang around asa half-remembered cult item that is a more ideal closing chapter for so-called New Hollywood than any of the movies that usual get credit for it. Technically a mid-1970s neonoir mystery with its mix of paranoia and cynical paralysis (although Passer himself admits that the mystery is its weakest point), Cutter’s Way is closer to a bitter comedy about counterculture hangover whose spirit of generous desperation resembles the films that Carlos Reichenbach made in Brazil at the same period.

I always associate Cutter’s Way with two other films released in the same period, Larry Cohen’s The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover and William Richert’s Winter Kills, transpositions of the American paranoid literature of the era (Pynchon, DeLillo) to picaresque historical panoramas sending off the country’s paranoid myths.Of all of them, Cutter is the most memorable because it is most human due to the affectionate portrayal of his marginalized environment.At its center, there’s the figure of Vietnam vet Cutter, who lost a leg and an arm in the conflict, resentful and obsessed with solving the sex crime who moves the action as a last social stand.Cutter is a sort of Travis Bickle without any of Hollywood’s attempts to gild the pill beginning with John Heard’s performance that is very expressive but devoid of seductive charisma that we associate with a De Niro (between Cutter and the main character of Chilly Scenes of Winter Heard dominated the figure of the self-destructive man at the turn of the 70s).That Cutter is right matters little next to how he just drags everyone around him into his fantasy of resentment.It’s one of the most powerful movies I know about the fictions we create to deal with our own powerlessness.